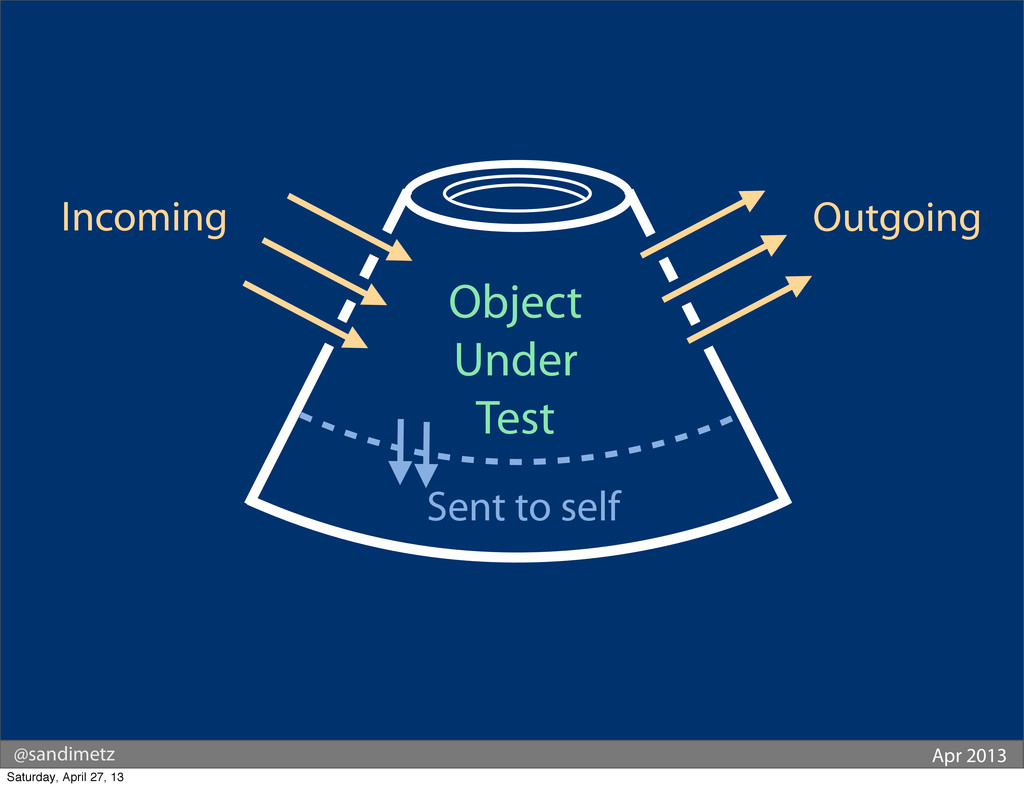

Look at the following image...

...it shows an object being tested.

You can't see inside the object. All you can do is send it messages. This is an important point to make because we should be "testing the interface, and NOT the implementation" - doing so will allow us to change the implementation without causing our tests to break.

Messages can go 'into' an object and can be sent 'out' from an object (as you can see from the image above, there are messages going in as well as messages going out). That's fine, that's how objects communicate.

Now there are two types of messages: 'query' and 'command'...

Queries are messages that "return something" and "change nothing".

In programming terms they are "getters" and not "setters".

Commands are messages that "return nothing" and "change something".

In programming terms they are "setters" and not "getters".

- Test incoming query messages by making assertions about what they send back

- Test incoming command messages by making assertions about direct public side effects

- Messages that are sent from within the object itself (e.g. private methods).

- Outgoing query messages (as they have no public side effects)

- Outgoing command messages (use mocks and set expectations on behaviour to ensure rest of your code pass without error)

- Incoming messages that have no dependants (just remove those tests)

Note: there is no point in testing outgoing messages because they should be tested as incoming messages on another object

Command messages should be mocked, while query messages should be stubbed

Contract tests exist to ensure a specific 'role' (or 'interface' by another - stricter - name) actually presents an API that we expect.

These types of tests can be useful to ensure third party APIs do (or don't) cause our code to break when we update the version of the software.

Note: if the libraries we use follow Semantic Versioning then this should only happen when we do a major version upgrade. But it's still good to have contract/role/interface tests in place to catch any problems.

The following is a modified example (written in Ruby) borrowed from the book "Practical Object-Oriented Design in Ruby":

# Following test asserts that SomeObject (@some_object)

# implements the method `some_x_interface_method`

module SomeObjectInterfaceTest

def test_object_implements_the_x_interface

assert_respond_to(@some_object, :some_x_interface_method)

end

end

# Following test proves that Foobar implements the SomeObject role correctly

# i.e. Foobar implements the SomeObject interface

class FoobarTest < MiniTest::Unit::TestCase

include SomeObjectInterfaceTest

def setup

@foobar = @some_object = Foobar.new

end

# ...other tests...

end

Yes, and further: it is important that the stub is async (if your language supports that). The fact it is a time-sensitive is a more important detail than things like api key and url or what it comes from.

Feels like you took a step forward, but now two steps back. The output of a class of type WeatherAPI does not depend on its input. The output depends on whatever the weather server says it does. We don't know that for certain with a guarantee that a machine would consider proof. For all we know it could be returning Rainy all the time and ignore your input (or your input parameter could be wrong).

This detail does not matter for the SUT of what-should-I-wear because no amount of fiddling will prove that it is correct with a production-level certainty.

This would not work. The test has to specify the Stub, so the test has to define what it returns when asked, ie. by default "Sunny", and only for London return "rain". Then you implicitly verify it was called correctly if the output is raincoat. So the information (default: Sunny, London: Rain) is part of the assertion and should be right next to it in the same test.

Yes, correct! This is on track now, you got it.

For that you need a zero-case for the behavior for some other form of clothing that isn't rainy. You are right if Sunny -> Raincoat and Rain -> Raincoat. That's why it is important that you compose these tests from sensible base tests (remember the two I added in my original reply?)

Yes and you picked up on it already. The difference is that the stub needs to exhibit the intended behavior. Let me zoom in all the way:

When you wrote the test originally you said the behavior is Rain -> Raincoat. There is zero location in that. London is not in any shape or form the correct answer. So the simplest test for that is assert(wearing("Rain"), "raincoat").

However, this is now just a simple map, and the information that the weather is async got lost. So the async bit has to come back. Let's compose it.

The inverse isn't super sensible:

whatShouldIwear = fetchWeather(wearing(location))So we keep the obvious one:

whatShouldIwear = wearing(fetchWeather(location))So far so good. You can now see that whatShouldIwear is a function of (fetched location). The SDK (or fetch API) are details. So the object becomes

Let's unpack this with a counter example. Let's say you put a "cache" in front of your outgoing query which is the WeatherAPI but it has the same interface. That cache returns "Rain" if it cannot access the server (ie. a unit test with an air gap) or if you flip a flag to not talk to external servers (ie. in CI mode).

This is sensible for the weatherAPI, but now none of our tests for ClothingPicker are failing or passing correctly. It also makes the question, "was the API called with London" completely non-deterministic because you don't know whether you got Rain because the location was passed or if you got Rain because the server is down.

This now exposes the core issue: You cannot write the test in such a way, that you could have the API be

pick(location)but not know the weather. So the location-to-weather mapping is intrinsically the main information needed, which is exactly what the collaborator provides. The collaborator doesn't "return Rain". It provides "Rain for London", if it is indeed raining in London. It's that second piece of the information that we're mocking, not the mapping itself.Now you ask, why is it not worth testing? Because if you want any code to execute at all, you need to call the real one. Because if you do not, then the only code executed is the creation of the mock, and the calling of a mock. In this case you fully ignore the fact that something has to be done with raincoat.

So your code becomes (pseudo code):

This breaks the determinism and structure-insensitivity on the test, because test has multiple falses:

Ultimately you cannot test the invocation of the method, without screwing up what it does with the return value in any way that would be more reasonable thangiving the SUT a simpler stub through the code.