As stated in the README of the git source code repository, Linus Torvalds came up with the name "git" and said that its meaning depended on your mood. It can stand for:

"global information tracker": you're in a good mood, and it actually works for you. Angels sing, and a light suddenly fills the room.

"goddamn idiotic truckload of sh*t": when it breaks.

If you want to see for yourself just how accurate this is, just google something like "why do people hate git" and you'll find plenty of funny (and desperate) comments and stories.

In this article, my goal is to introduce you to commands or actions that are really helpful but not that readily available. This list is the result of hours of googling, making experiments (occasionally breaking a repository beyond the point of repair), coming up with complicated workarounds only to find the right command a hour later and losing my mind seeing other people (and myself) do stupid things such as recreating an entire repo to get out of a mess or copying changes one by one. Hopefully, some commands will save you time and suffering, and maybe even convince you that git can really help you work more efficiently (and be super fun!).

Disclaimer: this is not an introduction to Git. It assumes that you are already comfortable with basic commands like git commit, git branch, git add, and so on, and have at least some familiarity with some more advanced stuff like git rebase. There are a lot of great tutorials to get you started. For example, the Pro Git book is available online, it's really clear and a lot of fun to read.

When you work with a repo that has more than one main branch, for example a branch for staging environments and another one for production, in some cases you'll need to copy files or changes from one to the other. Or you may have a branch with some very nice changes that you want to keep but with a completely ruined history that you'd rather throw away. You may also want to copy a file exactly as it was in a previous commit.

I've seen all kinds of painful workarounds to do this, such as making intermediate copies, copying changes from the browser, and so on. But the git checkout command already does this. Though it's mainly used to switch branches, it actually (as it says in the doc):

Updates files in the working tree to match the version in the index or the specified tree. If no pathspec was given, git checkout will also update HEAD to set the specified branch as the current branch.

In simpler terms, git checkout will bring changes from the specified version for the indicated paths. This means that to copy files from another branch or revision, you can just run:

~/test-repo$ git checkout $REF $PATHS$REF can be a branch, tag or commit, while $PATHS should include paths to all the files and/or directories that you want to "copy". For example, if you have updated the documentation in the staging branch (files in the docs directory and the README) and want to copy those changes to master, you can do the following:

~/test-repo$ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

~/test-repo$ git checkout staging docs README.md

Updated 3 paths from 0e1220e

~/test-repo$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: README.md

new file: docs/API.md

new file: docs/architecture.mdCopy-pasting just became much cooler.

If you're like most people, at some point you commited a file by mistake before adding it to .gitignore. And you probably tried to remove with git rm $FILE, only to find that it doesn't only remove it from your index but deletes it altogether. If you still need it locally, but no longer want it in your repo, just add the --cached flag.

So, for a single file:

git rm --cached path/to/fileAdd the -r flag to remove a whole directory:

git rm --cached -r path/to/directorySometimes, you'll run tests or other commands that send their output to files and directories inside you repo. As long as you don't add them to your index, these files will appear as untracked:

~/test-repo$ git status

On branch master

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

coverage.xml

test_report.xml

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)If you just want to ignore them, you can always add them to .gitignore, but in some cases you'll want to delete them. An easy way to get rid of them is running the following command:

~/test-repo$ git clean -f

Removing coverage.xml

Removing test_report.xmlIf you also want to remove untracked directories, just add -d.

WARNING: be careful before using this command because the deleted files cannot be recovered. If you want to perform a dry run to be absolutely sure of what it will delete, run it with the -n flag.

A .gitignore file inside a repository should only include files or patterns general enough to apply in most cases. For example, it makes perfect sense to ignore pycache files because they are always generated, but if you have a file with a name like squirtle_test, it's very unlikely that someone else using your repository will have a file with that name. In these cases, adding it would just pollute the .gitignore.

Fortunately, there are ways to ignore a file locally (without everyone finding out the name of your favorite Pokémon).

One option is to add the file name (or a matching pattern) to the .git/info/exclude file, which works as a .gitignore file but only for your local environment:

~/test-repo$ echo "squirtle_test" >> .git/info/excludeAnother option, if you want to ignore files that match this pattern in all your repos, is to add it to a global .gitignore file. Just create a .gitignore in your home directory:

~/test-repo$ echo "squirtle_test" >> ~/.gitignoreWhen you want to delete a commit, the obvious choice is to run git revert. This command creates a new commit that reverts the changes. Therefore, if you run git revert, your history will end up looking like this:

commit ff2471da509f8239e210bf5c9391a0dbf1867695 (HEAD -> master)

Author: muripic <[email protected]>

Date: Tue Aug 3 09:05:38 2021 -0300

Revert "Add environment variables"

This reverts commit d93f84d5127cf012a26b72870c513c3171166c18.

commit d93f84d5127cf012a26b72870c513c3171166c18

Author: muripic <[email protected]>

Date: Tue Aug 3 09:03:59 2021 -0300

Add environment variablesThis means that the changes in the unwanted commit will still be accessible, and this could be a problem if you committed sensitive information, or maybe you just want to keep your history nice and clean. If your branch is not protected (you can check this in the repository settings in your git hosting service), you can perform a rebase and delete those commits instead. To do this, run:

~/test-repo$ git rebase -i HEAD~3The HEAD~3 reference will let you edit the last three commits. You can choose other types of references, such as the source branch or a particular commit hash.

After running this command, you will see a list of commits in your configured editor. You'll also see that on the left it says pick. Replace pick with drop for the commits you want to delete, and save.

pick e2532d3 Update README

pick 01050cd Add documentation

drop a51d899 Add environment variables

# Rebase ff2471d..a51d899 onto ff2471d (2 commands)

#

# Commands:

# p, pick <commit> = use commit

# r, reword <commit> = use commit, but edit the commit message

# e, edit <commit> = use commit, but stop for amending

# s, squash <commit> = use commit, but meld into previous commit

# f, fixup <commit> = like "squash", but discard this commit's log message

# x, exec <command> = run command (the rest of the line) using shell

# b, break = stop here (continue rebase later with 'git rebase --continue')

# d, drop <commit> = remove commit

# l, label <label> = label current HEAD with a name

# t, reset <label> = reset HEAD to a label

# m, merge [-C <commit> | -c <commit>] <label> [# <oneline>]When the rebase is finished, if you run git log, you'll see that the commit disappeared:

~/test-repo$ git log --oneline

01050cd (HEAD -> staging) Add documentation

e2532d3 Update README

cd2af11 Initial commitAlthough this method allows you to delete any commit, if you delete commits in the middle of your history, there may be conflicts. It can still be done, but it take more time and effort. If you don't want to deal with this problem, just abort the rebase with git rebase --abort. Everything will go back to where it was and you can do the revert instead.

Forgot a tiny change or found a typo? Make the changes, stage them with git add and run:

git commit --amend --no-editIf you want to edit the commit message, just remove the --no-edit flag and an editor will open for you to modify it.

If you need to edit a previous commit instead, this method won't work. In that case, use git rebase -i, and when the editor opens replace pick with edit to make changes or just reword to rewrite the commit message.

Had a bout of insomnia and worked until 2 AM but don't want anybody to find out? Do you use your commit timestamps for reports or stats and at some point you performed a rebase that left your timestamps inconsistent with your git history?

Just as with any command used to edit the history, the possibility to do this will depend on whether your changes have been already pushed and, if they have, if the remote branch is protected or not.

Also, it's important to bear in mind that commits have two timestamps, a "git author date" and a "git committer date". For more info about this difference, check out this StackOverflow thread.

If you just need to change the author date in your last commit, run:

git commit --amend --date="Wed Aug 4 00:00:00 2021 -0300" --no-editThe edited commit will look like this:

~/test-repo$ git log --format="[%h] Author date: %ad, Committer date: %cd, Message: %s"

[aa0b6c6] Author date: Wed Aug 4 00:00:00 2021 -0300, Committer date: Wed Aug 4 07:18:52 2021 -0300, Message: Update README(I'm using a special log format to see both dates, since only author date is shown in the default logs. More on this later!)

To change both timestamps, do this:

~/test-repo$ export GIT_AUTHOR_DATE="Wed Aug 4 00:00:00 2021 -0300"

~/test-repo$ export GIT_COMMITTER_DATE="Wed Aug 4 01:01:01 2021 -0300"

~/test-repo$ git commit --amend --no-editIf we run the same log command, we can see that in this case the committer date has changed too:

~/test-repo$ git log --format="[%h] Author date: %ad, Committer date: %cd, Message: %s"

[d9129e1] Author date: Wed Aug 4 00:00:00 2021 -0300, Committer date: Wed Aug 4 01:01:01 2021 -0300, Message: Update READMEFor more complex cases, such as editing the timestamps of previous commits, you will need to perform an interactive rebase. Run git rebase -i REF and when the editor opens, replace pick with edit. When the rebase process stops to let you make changes to the commit, edit the timestamps with the commands shown above. After changing the dates, continue your rebase with git rebase --continue.

git log must be among the most popular git commands. Along with git status, it gives you most of the information you need to know where you're coming from, where you are, and hopefully where you're going. But the functionality of git log is supercharged when you add format options.

There are plenty of options, which you can see running man git-log. I'll only list some that I think show how useful this feature can be:

git log --oneline: shows commit title, short hashes, and other refs, one per line. This is very useful if you want to see the history without scrolling too much.git log --date=relative: if you don't know which day it is or don't care, and just want to see how long something has been broken.--date=unixor--date=isocan be very useful if you need to parse these dates.git log --format=<string>: the format flag allows you to format your commits in printf style. This is extremely flexible since there are plenty of placeholders and format options to choose from: check out thePRETTY FORMATSsections inman git-logfor a full list. It may be a little too complicated for everyday use, but it can save you a lot of time if you need to parse the output. Also, you can find a couple of formats that work for you and keep them in hand.

Here are two example formats, for very different purposes:

git log --format="%s|%h|%an|%ae|%at": this shows the commit message, short hash, author name, author email and unix timestamp, all separated by a pipe, which makes it very convenient for parsing.git log --format="[%h] %an committed %s at %aD": a format like this one, on the other hand, is better for purposes such as chat integrations or notifications, since it shows the commit message and author in a human-readable format.

Deep down, a git repo is a graph (check out think-like-a-git's section on graphs, and all the other sections which are just as awesome, if you're feeling adventurous.) When you work on a very complex repo, with lots of branches and contributors, seeing it as a graph can help you sort things out.

Again, git log to the rescue:

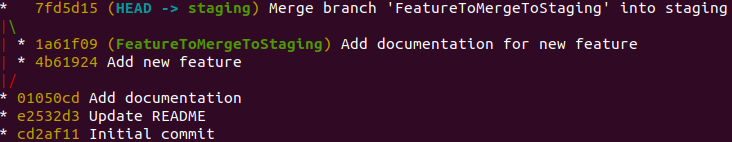

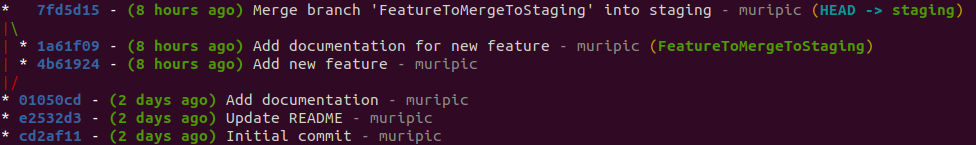

git log --oneline --graphThe --graph flag can be combine with --format, which leads to a world of possibilities. You can experiment with different formats and colors. Here are two very nice examples (taken from this StackOverflow thread, with slight changes):

git log --graph --abbrev-commit \

--format="%C(bold blue)%h%C(reset) - %C(bold green)(%ar)%C(reset) \

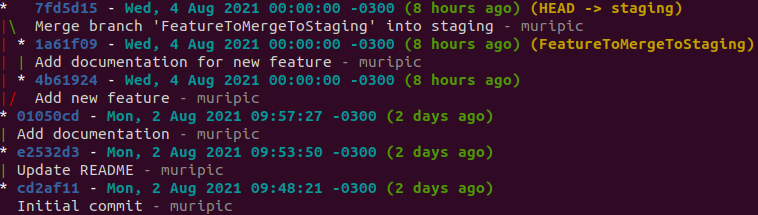

%C(white)%s%C(reset) %C(dim white)- %an%C(reset)%C(auto)%d%C(reset)"git log --graph --abbrev-commit \

--format="%C(bold blue)%h%C(reset) - %C(bold cyan)%aD%C(reset) \

%C(bold green)(%ar)%C(reset)%C(bold yellow)%d%C(reset)%n""%C(white)%s%C(reset) \

%C(dim white)- %an%C(reset)"We continue with git log; it has so many flags with so many different functionalities that they can be considered subcommands.

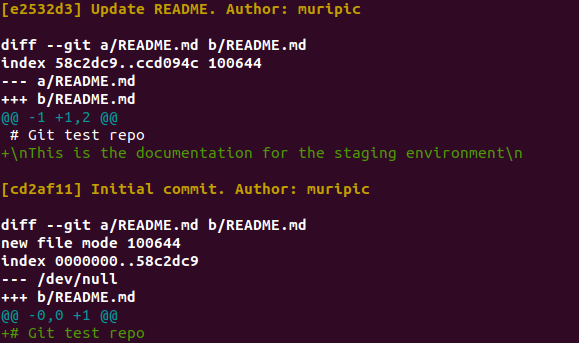

If you want to see the history of commits that modified a particular file, as usual, git log has you covered. Run:

git log --followHere's an example using some of the formatting options that git log provides:

~/test-repo$ git log --follow --oneline --format="[%h] %s. Author: %an" README.md

[e2532d3] Update README. Author: muripic

[cd2af11] Initial commit. Author: muripicAdd -p to show the diffs too (plus some extra formatting to improve readability):

~/test-repo$ git log -p --follow --oneline --format="%n%C(bold yellow)[%h] %s. Author: %an" README.mdIf you want to see who have contributed the most to the repository, git shortlog can show you. As the documentation says, this command "summarizes git log output in a format suitable for inclusion in release announcements. Each commit will be grouped by author and title." It will output something like this:

~/test-repo$ git shortlog

cosmefulanito (1):

Add tests

muripic (4):

Initial commit

Update README

Add documentation

Add new featureAs is usually the case with git commands, there are plenty of flags available. Some of the most useful ones are:

-nor--numberedwhich will sort the output according to the number of commits per author, in descending order (default is alphabetical order).-sor--summary, which only show the commit count, without the commit description.--sinceand--until, which will only consider commits between the specified dates.

For example:

~/test-repo$ git shortlog -s -n

4 muripic

1 cosmefulanitoIn some cases, mostly in legacy projects without proper CI, a commit that introduces a bug or causes an issue that will go unnoticed for some time, and when it's finally discovered, many more changes have been made and it can be difficult to pinpoint the one that caused the problem. git bisect was created

with these situations in mind:

This command uses a binary search algorithm to find which commit in your project’s history introduced a bug. You use it by first telling it a "bad" commit that is known to contain the bug, and a "good" commit that is known to be before the bug was introduced. Then git bisect picks a commit between those two endpoints and asks you whether the selected commit is "good" or "bad". It continues narrowing down the range until it finds the exact commit that introduced the change.

Although it's mostly used for commits that introduce bugs, it can be used for any kind of change. The terms "good" and "bad" can even be replaced to account for these uses, but I won't go into such detail here; run man git-bisect if you want to know more.

For example, imagine you want to find the commit that broke some tests that aren't run with the build. Run:

~/test-repo$ git bisect start

~/test-repo$ git bisect bad # Current version is bad=tests are broken

~/test-repo$ git bisect good 1w0u1dn3v3rc0mm1tbr0k3nt3sts # This was your last commit

# and you would never ever commit

# without making sure all tests passNow, you are standing on commit 1w0u1dn3v3rc0mm1tbr0k3nt3sts. Run your tests.

Everything is ok (of course, because this was your commit). Tell this to git with git bisect good.

You'll see that git moves forward in your history and shows you a message like the following.

Bisecting: 2 revisions left to test after this (roughly 2 steps)

[th1sc0mm1tc0u1db3v3rybr0k3n] Merge pull request #104 from someonesbranch

Run your tests again. If they fail, let git know with git bisect bad. If they don't, run git bisect good again. You get the idea.

Repeat this until you get a message like the following:

1obv10us1yd1dn1runa11th3t3s1s is the first bad commit

commit 1obv10us1yd1dn1runa11th3t3s1s

Author: Mr. Magoo <[email protected]>

Date: Sun Jun 6 17:31:06 2021 +0300

Make some possibly destructive changes

src/app/main.go | 25 +++

1 file changed, 25 insertions(+)

Go back to the original HEAD with git bisect reset and clean up the mess or go get Mr. Magoo so he can fix it himself.

I hope that at least some of these commands start making your version-control-related life easier, and that you start enjoying git a bit more than before.

Want more? List is not over yet: git has a lot more to offer, so part II is coming soon :)