This guide aims to teach the most primitive concepts of Javascript, and is adressed to any people with a minimum knowledge of programming. This guide won't focus on ES6 specificities or any shorthand / advanced syntax.

Use cases of each notion are isolated and won't mix too much notions in order to focus on the current notion.

Variables are used to temporarily store values under a name that describes the value it is holding. There are different types of variables:

variable = 10;

/* ^^^^^ ^^

name value

*/variable is not declared with a keyword such as const, let or var

and is thus considered as a global variable. It means its scope is global and it can be

accessed from anywhere.

Don't use global variables unless you really have a good reason to.

Three keywords can be used to declare variables.

var is the most basic one but also the oldest, and suffers of misconception on very

specific edge cases. A variable can be redeclared with the use of var, but don't do that.

var age = 10;

var age = 12; // Works but don't do that.

age = 12; // Do that instead if you need to reassign.let was introduced in ECMAScript 2015 (Javascript version), more commonly called ES6. Variables

declared with let can be reassigned and have the same behaviour than var, except it is safer

to use as you can't redeclare a variable that is already defined, and its scope is also

reduced to what we can call a block. A block represents a portion of code, usually written

between curly braces (or curly brackets) ({}).

// Level 0 scope. This variable can be access to all scopes under this one.

let foo = 10;

if (1 < 3) { // Here we enter in a block thus a new scope

// Level 1 scope. We have access to variables declared on the upper scope

let foo = 12; // This is valid, and redeclares foo for this scope

console.log(foo); // Outputs 12

// End of level 1 scope

}

console.log(foo); // outputs 10You can't redeclare a let variable within the same block:

let bar = 4;

let bar = 5;

// Uncaught SyntaxError: Identifier 'bar' has already been declaredconst was introduced aswell in ECMAScript 2015, but unlike let and var, const variables

can't be reassigned*. Variables declared with const can't be redeclared either.

*We'll see later that we can modify an object declared with const's properties, but

not the variable itself.

const baz = 5;

baz = 5

// Uncaught TypeError: Assignment to constant variable.var is an old keyword and shouldn't be used anymore. Focus on using let and const instead.

If you need to inspect or read a variable to see what value it is holding, you can make use of the

function console.log.

const foo = 5;

console.log(foo);

// Outputs:

// 5You can pass multiple variables to inspect to console.log:

const foo = 5;

const bar = 'bar';

console.log(foo, bar);

// Outputs:

// 5 barThere are several types of variables:

- numbers

- strings

- booleans

- arrays

- objects

- functions

- null

Numbers are written as is. They don't need a specific character to indicate it is a number. Decimal values are written after a dot.

const foo = 10;

const bar = 10.5;Strings represent text. A string is delimited by matching quotes, either double or single, or by backticks:

const foo = 'This is a string';

const bar = "5"; // This is not a number, it is a string

const baz = `This is also a string`;Booleans are a type whose values can either be true or false. They are often used to indicate

the state of something:

const isOld = false;

const isTall = true;Arrays are lists that can contain 0 to n values. They are ordered and values are accessed

by their index, starting from 0 for the first item. Arrays are declared with square brackets ([]).

const list = [5, 'some string', true]; // Arrays can have any type of value

console.log(list[1]); // Outputs: "some string" as it is 0 indexed

console.log(list.length) // Outputs the number of items in this array: 3

const list2 = []; // Arrays can be empty

const listception = [1, [2, 3], [[3]]]; // Arrays can have sub-arraysFor consistency, we prefer having arrays whose values all have the same type or shape.

Objects are a special type very commonly used. They aim to give a structure to data, or to

represent things with multiple properties. They are declared using curly braces ({}) and are

composed of key-values entries.

Keys must be strings or numbers, while values can have any type, even object.

const dog = {

name: 'Milady',

age: 13,

isSick: false,

};

const person = {

name: 'John Doe',

phone: { // Object under object

mobile: '(+33)6 01 02 03 04',

home: '(+33)1 02 03 04 05',

},

};Objects' values are not ordered unlike arrays, and the order of properties at the moment we write them doesn't matter on the end result.

To access properties within an object, we use the dot notation . to traverse the object.

const person = {

name: 'John Doe',

phone: {

mobile: '(+33)6 01 02 03 04',

home: '(+33)1 02 03 04 05',

},

};

console.log(person.phone.home);

// Outputs

// (+33)1 02 03 04 05When we want to have access to a property whose name is stored in a variable, we need to use the square brackets notation to dynamically access this property.

const phoneType = 'mobile';

const person = {

name: 'John Doe',

phone: {

mobile: '(+33)6 01 02 03 04',

home: '(+33)1 02 03 04 05',

},

};

console.log(person.phone[phoneType]);

// Outputs

// (+33)6 01 02 03 04Objects also have the singularity of having mutable properties. It means their properties can be

reassigned, even if the object is declared with the const keyword.

const person = {

name: 'John Doe',

phone: {

mobile: '(+33)6 01 02 03 04',

home: '(+33)1 02 03 04 05',

},

};

person.name = 'Jane Doe'; // This works.Functions are considered a type, but I'll dedicate a section to functions, as it is a very important notion of programming.

The keyword null is used to express the fact that a value is either empty or doesn't exist.

Unlike undefined, null is a value that represents nothing as something where undefined

represents nothing as nothing.

const bottle = {

volume: 0.75, // Can also be written .75

unit: 'L',

label: null,

};

console.log(bottle.label);

// Outputs: null -> Bottle has no label, this is probably some of grandpa's suspicious alcohol

console.log(bottle.wings);

// Ouputs: undefined -> What wings ? I don't know about wings, it doesn't exist.Conditions allow to execute code depending on what an expression evaluates to.

const limit = 10;

if (5 < limit) { // We enter in a block

// Execute some code here

console.log('5 is under the limit.');

}Code inside the condition block is executed only if the expression inside the parentheses evaluates to a truthy value. You can read more about truthy and falsy values here.

You can also enumerate other conditions if the first one is not fulfilled.

const speed = 40;

if (speed < 30) {

console.log('You\'re slow, stay safe');

} else if (speed <= 50) {

console.log('You\'re ok but don\'t drive too fast in town');

} else if (speed < 130) {

console.log('I hope you\'re on a highway');

} else { // Executed if speed is superior to 130

console.log('Yo calm the fuck down');

}There is another way to use conditions, but this method is acceptable only if the code to execute holds on a single statement, or is simple enough. This method is called ternary and is often used for conditional assigments.

const isInTown = true;

let maximumSpeed;

if (isInTown === true) {

maximumSpeed = 50;

} else {

maximumSpeed = 90;

}

// Can also be written as

const maximumSpeed = isInTown ? 50 : 90;

// ^^^^^^^^ ^^ ^^

// expression || else block

// if blockSometimes, to enter a condition you need to make sure that multiple conditions are respected so you can execute code. To do this we have two main boolean operators that allow us to express such complex things.

- OR operator (

||) -> Ensures at least one condition is respected - AND operator (

&&) -> Ensures all conditions are respected.

const speed = 110;

const isInTown = false;

if (speed > 50 && isInTown === true) {

console.log('Woaw, slow down this is not safe');

} else {

console.log('You\'re probably on a highway, but not sure about that');

}Functions are blocks of code that are meant to be reused multiple times at any place. We use functions in different cases.

- It reduces code duplication

- It hides logic away from the main code

- It allows splitting code to make it more readable.

Functions can be declared in many ways, but we'll focus on the main way of creating one.

A function has a name, and can take a list of parameters. A function is not executed until it is called.

function greet(name) {

console.log('Hello ' + name);

}

// Here we call the function with its only parameter

greet('John'); // Ouputs: "Hello John"Here, we declared a function called greet that outputs Hello {name}. name is a

parameter. This parameter is replaced by the value provided when we call the function.

This way, we can greet multiple persons in a row:

greet('Jane');

greet('John');

greet('George');Calling this function three times allowed us to reduce the code written, but also hides away from the developer what's behind the logic of greeting. In that case it is not that much, but functions usually hold more lines with generic logic. Generic means the code can be used to achieve the same result, regardless of the context.

By definition, an algorithm is a suite of statements that takes in input none or a defined number of parameters, and whose output should always return the same value.

A function is somehow an algorithm. It can take parameters, and can return values.

For example, we can write a function that takes a number for input, and that returns this value multiplied by 5.

function timesFive(input) {

// Notice the `return` keyword

return input * 5;

}

const result = timesFive(10);

console.log(result); // Outputs: 50The return keywords means that the function will give something in return, the result

of the function.

We can affect the return value of a function to a variable. If return is omitted, the

function returns undefined.

Loops are a way to execute a suite of statements an indefinite number of times until a condition is respected. It is mainly used to apply actions on every elements of an array.

There are two types of loops:

- For loops

- While loops

While both loops have the same goal, while loops are in general used to perform an

action n times while the end condition is not respected. We usually don't iterate

over arrays with a while loop.

while (Math.random() < 0.9) {

// ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

// This is the end condition. The loop will end when this condition evalutes to false.

console.log("I'm stuck in this loop because Math.random returned a number < to 0.9");

}

console.log("I'm out of the loop !");

// Ouputs

/*

I'm stuck in this loop because Math.random returned a number < to 0.9

I'm stuck in this loop because Math.random returned a number < to 0.9

I'm stuck in this loop because Math.random returned a number < to 0.9

I'm stuck in this loop because Math.random returned a number < to 0.9

I'm stuck in this loop because Math.random returned a number < to 0.9

I'm stuck in this loop because Math.random returned a number < to 0.9

I'm stuck in this loop because Math.random returned a number < to 0.9

console.log("I'm out of the loop !");

*/As we can't predict the output here over, we used a while loop to log that we're stuck in the loop until we reached out of it.

for loops are more often used to iterate over arrays and to execute the same action

over each element.

A for loop is composed of 3 elements:

- Definition of the incrementor (starting value)

- Stay in loop condition

- Loop end statement

The starting value usually is the starting index of the array, often set at 0 as it's

the first element of an array, but it can be anything else. Iterators are variables we

use to locate where we are in the loop. We usually name them by a letter starting

at i (i, then j, then k etc) then going onto the next one whenever we have a

loop in a loop.

The stay in loop condition has the same behaviour than the while loop.

The loop end statement usually increments the starting value in order to prevent infinite

loops, and to iterate over the next item in the array. If we start with i = 0,

then an end loop statement might look like something like i++ or i += 1 (append 1

to i).

const guests = ['John', 'Laura', 'Dirk', 'Farah', 'Anna'];

/*

- Starting value: 0;

- Stay in loop condition: `i` is inferior to guests' length

- End of loop statement: append one to i

*/

for (let i = 0; i < guests.length; i += 1) {

// Remember our function greet from above

greet(guests[i]);

// Here we access each guest name by their index in the list, aka `i`

}

/*

Outputs:

Hello John

Hello Laura

Hello Dirk

Hello Farah

Hello Anna

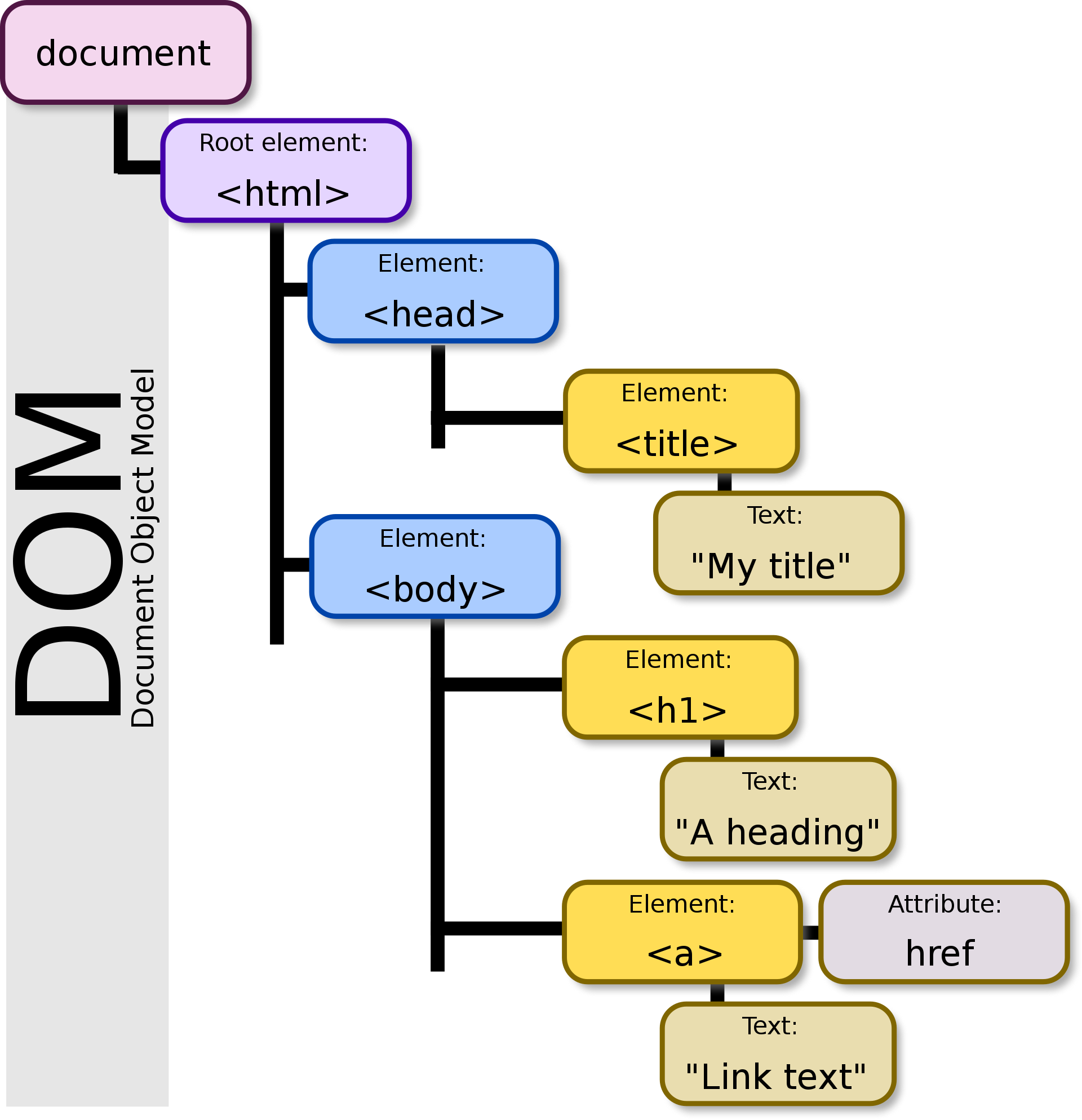

*/DOM (Document Object Model) represents an HTML document with trees and nodes for each element.

It can be represented as follows:

Each element can have one or multiple nodes, and each node is composed of a multitude of properties, such as attributes, style, or methods (actions bound to elements).

Whenever we need to manipulate the DOM with Javascript, we first need the page to be loaded in the browser to start querying elements.

window.addEventListener('load', function() {

// ^^^^^^^^^^

// Notice the function here. This is an anonymous function, it has no name.

// This is called a `callback`. This is a function that is called later, in this case

// when page did load.

console.log('Page has loaded');

});Now that our page has loaded, we can start querying for elements. We will use the following HTML template for the examples.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Manipulating the DOM</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Manipulating the dom</h1>

<p>This is a paragraph</p>

<p>This is another paragraph</p>

<p>We can have as many paragraphs as we want</p>

<div class="content">

Here we have a div with a class

</div>

<section id="article">

And a section with an ID

</section>

</body>

</html>So we want to do things with the heading element of this page (h1). To retrive an element,

we use the function document.querySelector(). It takes as parameter a CSS selector.

(ex: h1, .list li.underline...)

Note: This function will return ony the first HTML Element it will find in the tree, if

it finds one. It will return null otherwise.

window.addEventListener('load', function() {

const heading = document.querySelector('h1');

console.log(heading);

// <h1>Manipulating the dom</h1>

});So this way we managed to store our heading in a variable. What can we do with it ?

We can read its properties, such as its innerText. A more complete list of an Element's

properties is available on the MDN.

console.log(heading.innerText); // Outputs: Manipulating the DOMBut what we can also do is modifying it's properties ! We could change its content, or even its style !

window.addEventListener('load', function() {

const heading = document.querySelector('h1');

heading.innerText = 'I have manipulated the DOM';

heading.style.color = '#ff0000'; // Red

});When we want to query every elements matching a CSS selector, we need to use

document.querySelectorAll() instead. Unlike document.querySelector(), this function

will return an array, regardless of the number of items it matched. That means

the array can be empty.

window.addEventListener('load', function() {

const paragraphs = document.querySelectorAll('p');

// Outputs: NodeList(3) [p, p, p]

// We have a list, so we can iterate over this list to change each paragraph

for (let i = 0; i < paragraphs.length; i += 1) {

paragraphs[i].style.color = '#00ff00'; // Green

}

// This code works even if the list is empty.

// As 0 (starting value) < paragraphs' length is false, it will not enter the loop.

});